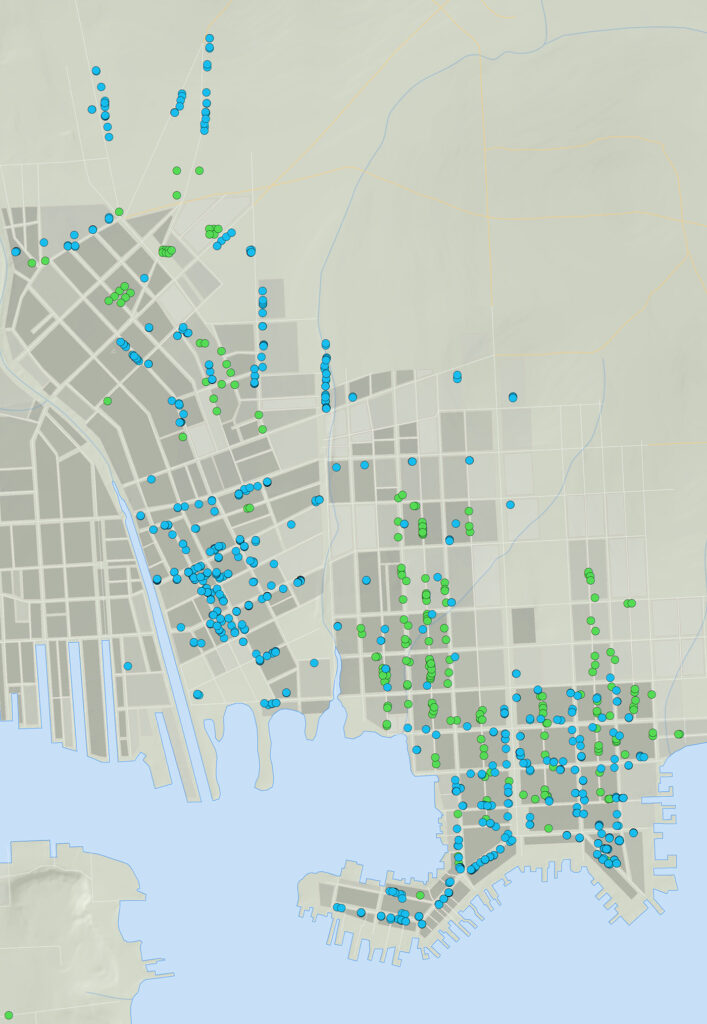

This project seeks to recover the lives of early Baltimore’s African Americans, both free and enslaved and to represent them both narratively and spatially. We do this by telling the stories of individuals whose lives we piece together from scraps of data found in public records and newspapers. We have put these stories into four broad thematic categories, sometimes visualized in different colors:

- Free Blacks (green)

- Enslaved Workers (blue)

- Slave Trade (orange)

- Fugitive Slaves (red)

- Whites are not the focus of stories but may sometimes be color-coded in purple.

These thematic categories are not strictly bounded — that is, a story about an enslaved worker could intersect with one about the slave trade, or a free black relative. As much as possible we want to capture the messy complexity of life in Baltimore two hundred years ago.

Finally, these stories are all works in progress, not complete narratives.

Sample Stories

The Diverse Residents of Strawberry Alley

While the population of whites, free blacks, and enslaved workers was relatively equally distributed across Baltimore’s 12 wards, the degree of integration varied within individual wards or neighborhoods. Strawberry Alley, in Fells Point, is a powerful example of this. Fells Point was home to much of Baltimore’s maritime industry, lined with wharves and shipyards, its streets filled with artisans like carpenters and caulkers, sailmakers, and riggers. According to city directories and tax records, the alley was home to 46 free blacks, 21 whites, and 1 enslaved worker. This diverse population allows us to explore the lives of free blacks as workers and, in particular, free black women. We can talk about the reasons that free black women chose to run their businesses out of their own homes (laundries especially) rather than work as domestics for white bosses. We can also consider the kinds of housing available to free blacks. Finally, there is some evidence that skilled workers lived on the main streets of Fells Point while unskilled workers lived in the smaller alley houses, and we can tease those relationships out.

Buying, Selling, and Hiring Enslaved Workers on Baltimore Street

Baltimore Street, formerly known as Market Street, was the heart of Early Baltimore’s commercial district. It was lined with merchant houses and dry goods stores, confectioners and millinery shops, silversmiths, and booksellers. Nor was it exclusively the purview of whites. African-American bootblack and varnish manufacturer Don Carlos Hall (the subject of theme 4) worked in the basement of 124 Baltimore, below Marmaduke Wyvill’s merchant tailor shop. Two black laundresses, Leah Sampson and Hester Foot, washed clothes west of Pearl Street. As the main commercial thoroughfare of the city, Baltimore Street was also inextricably linked to the institution of slavery. We know that 123 enslaved people lived and worked on Baltimore Street and that these people were owned by 54 different white people. And, because Baltimore did not have a central slave market, it was also a site of the slave trade. This thread will highlight ten advertisements (for sale or hiring) linked to shops, homes, or inns on Baltimore Street. These advertisements show that the bulk of Baltimore’s slave trade was local but also captured the rise of Maryland as an exporter of slaves to the cotton South, as demonstrated in an ad placed by an out-of-town trader searching for “from 30 to 40 Negroes.”

Don Carlos Hall, Free Black Businessman

Don Carlos Hall was a well-known free black businessman, described as a bootblack and varnisher. Hall lived on Salisbury Street near Exeter Street and worked in the basement of 124 Baltimore Street. He appears in the 1818 tax records as the owner of two acres of land on New Harford Road, which he appears to use to manufacture his product. Finally, Hall was one of the original founders of Baltimore’s Bethel AME church, the first African American church in the city and an important political and cultural institution for Baltimore’s free blacks. The church, founded in 1816, actually met briefly in Hall’s home before moving to its building. This thread allows us to tell two stories: First, a spatial story about the ways that free blacks traversed the city, moving from Hall’s home to his varnish manufactory, to his shop, and to his church. Second, we will use this thread to tell the story of the founding of Bethel Church and its significance.

Enslaved Workers at William Price’s Shipyard

The lives of individual enslaved workers are the most difficult to excavate from nineteenth-century sources. These people are rarely named in government documents (for example, the 1820 census sorts people into categories by sex and age cohort only). Baltimore’s 1813 and 1818 Tax Assessor’s Lists actually enumerated enslaved people by name and age, although chillingly, it did so to assign a value to them.

This allows us to map individual enslaved people in the same ways as we map free blacks and whites. Baltimore’s largest slaveholder in 1820 was William Price, a shipbuilder whose shipyard was located on Pitt Street in Fells Point. In 1818, 21 people were owned by Price, ranging in age from 70-year-old Bill Fisher to one-year-old Susan. Six women, ranging in age from Old Bet, 55, to 15-year-old Till, may have worked in the Price household, cared for children, or cooked for the men who worked at the shipyard. Nine men worked in the shipyard, probably alongside free blacks and whites, all of whom performed different work. Finally, Price also owned four boys under age 13 and two girls under six. This thread will center on the lives of these workers.

Imaging Research Center, UMBC © 2024